Are You Learning Or Just Copying?

Spending as much time as I do – enjoyable time, to be sure – transcribing and playing along with the solos by my musical idols of the moment, I sometimes have to stop and question whether I am making the best use of the (unfortunately) limited time I have for practicing.

To begin with, there is always the question of whether I should be writing instead of learning. The answer to that may well be “yes”, but I don’t seem to be in a writing mood these days – being a software developer and editor of Woodsheddin’ rarely leaves me with enough concentration for writing. But learning solos and licks is something I can do whenever I have a spare hour.

OK, but what do you do with those licks? Well, to be sure, I use them literally in performance as I play “Night and Day” a la Django or “Road Song” a la Wes. And you get several pure benefits just from doing the work of transcribing and practicing up to speed. The act of transcription extends your musical vocabulary. I often come away with a sense of “I didn’t know you could get away with that” after transcribing some killer-sounding passage that completely violates whatever harmonic logic I’ve absorbed through the years. It’s a liberating feeling, like being given permission to go beyond the world of formal rules about what’s right and wrong, and to play in the world of pure imagination. Even if emulating someone playing from that place doesn’t get you there, it reminds you that the place and the feeling exist.

Emulation is also great for your chops. Getting your fingers to move in patterns that are unfamiliar, often at challenging speeds, expands your physical capabilities and breaks you out of ruts. If your muscles evolve to where they are comfortable moving like Wes Montgomery (or Art Tatum or John Coltrane or Jimi Hendrix), then your spontaneous improvising is likely to drift in those directions on occasion. A gradual process of integrating new sounds and new approaches with your own playing style is bound to occur if you just play the new riffs enough and naturally listen more carefully to everything as you get deeper into one thing.

This article is about what we can do to consciously accelerate that kind of integration.

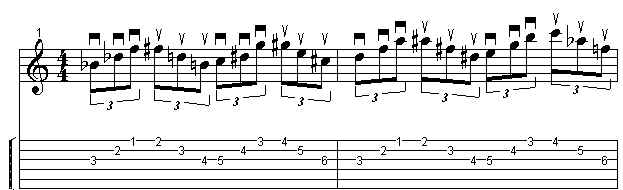

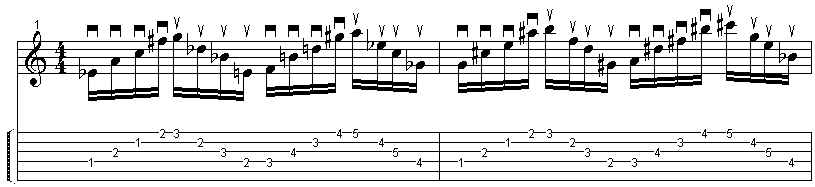

Mainly the process involves actually thinking about what I’m doing and, in a practice situation, extracting the essence of a riff (i.e., answering the question, “just what is it about this passage that appeals to me so much?”), and applying it in a new context. Well, gosh, this is suspiciously like work. And, in fact, it is work, but the rewards are substantial and lasting.Let’s look at two examples for now: two little fragments of riffs, one from Wes and one from Django (also used by violinist Stephane Grappelli).

Interestingly enough, both of the examples that I am drawn to look at are essentially ornaments – ways of hitting a particular note that involve “beating around the bush” a little bit by trilling or slurring the adjoining notes before settling into the target. As all classical players know, ornaments are key elements of various musical styles. The way you play the ornament around a single note can determine whether you’re playing in a Renaissance, Baroque or Classical style – or, in our case, whether you sound like a bluesman or a gypsy.

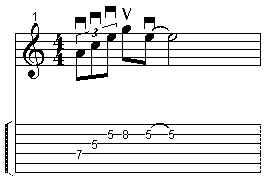

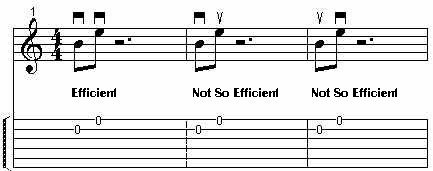

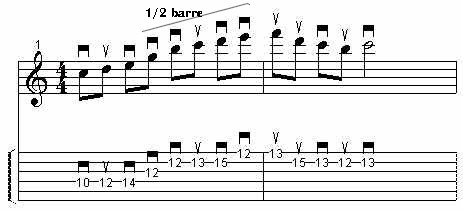

Look at the first ornament, taken from the first turnaround of Wes’ Montgomery’s solo on Road Song, from the CD Jimmy & Wes, The Dynamic Duo (click here for more about the CD and the solo), shown here (the song is in Gm):

I was drawn to thinking about this element simply because it feels so good to play. If you’re playing in a jazz context, throwing this riff in just says “blues”. So, the question is, where does it work best? When should you use it?

Being the brute-force kind of experimenter guy that I am, I figured the best way to approach this would be to put a major and minor blues progression onto tape (well, actually I used an Echoplex looper, but that’s just ’cause it was convenient), to play phrases involving the ornament on top of it, and to see what works. And I made it even simpler for myself: I just played the first five notes (together with the grace note at the start). The phrase eventually, as I tried to apply it, got even shorter, until I was using just the first three notes (plus the grace note).

What I learned is simple: this sounds great practically in any part of a blues progression, major or minor, as long as you start on the fourth degree of the scale. So, in a Gm progression, start the trill on a C. In E, start in on A.

Oh yeah, there’s one other thing to keep in mind – although it’s great, during practice, to play the ornament a zillion times, wherever it fits (or even where it doesn’t fit), you should use it far more sparingly when actually performing. If you sneak it in a few times (or even just once!) in an evening, it can add a bit of spice without becoming a cliche.

By the way, another key stylistic element of Wes’ playing that I discovered while transcribing and analyzing is the fact that he almost always uses a half-note interval when sliding into an octave from below – almost never a whole step or other interval. And he does quite a bit of this sliding.

In the next issue of Woodsheddin’: we’ll apply this method to the “gypsy trill” beloved of Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli.

etc.

etc.

etc.

etc.