Gypsy Jazz Ornaments

In an earlier article, “Are You Learning Or Just Copying”, I advanced the idea that ornaments are essential elements of any style, and that copying ornaments from records and applying them to new situations is a great way of evoking the feel of a style.

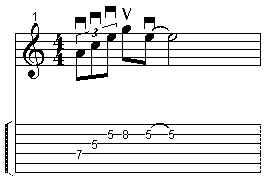

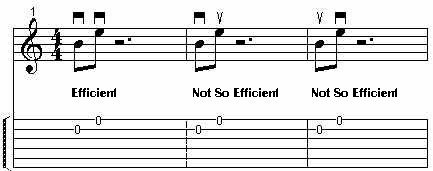

This observation applies especially to jazz in the style of Django Reinhardt, who utilized ornaments called “enclosures” extensively. In a previous article, we analyzed and reapplied a Wes Montgomery ornament. In this article, we’ll give the same treatment to what I call a variant or two as encountered on recordings. (Turn: An ornament consisting of four or five notes that move up and down ‘around’ a given pitch, using that pitch as a tonal center. It is often referred to as an enclosure.). The first turn is a grace note triplet preceding a “target note” (C, in the following example), like in the first measure of this example:

The second measure shows how the turn is more typically extended and resolved (by continuing the chromatic motion for one more step up, and then continuing with whatever the melody needs to do); so the actual turn is really 5 notes: 3 grace notes and 2 eighth notes.

In practice, Grappelli tends to really play the first triplet as grace notes, while Reinhardt is more likely to steal more time from the preceding note.

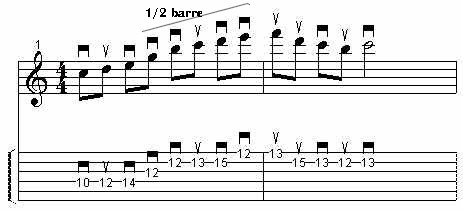

For instance, in the version of “Nuages” on Django Reinhardt: Verve Jazz Masters 38, Grappelli plays the third and fourth phrases like this:

In this case, the A in the third measure is preceded by three grace notes (not shown): Bb – B – Bb.

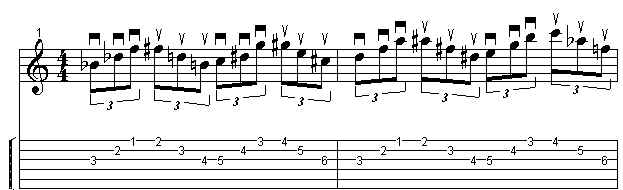

Here’s another example of the trill, from the beginning of Night and Day’s head, from the same CD. This time Django is playing:

In this case, the three grace notes have been expanded to take up a full beat (I’m exaggerating, and the true timing is somewhere between these two extremes). But the form remains the same: it’s a turn leading to the G on the fourth beat of the second measure, and then the chromaticism is extended, as the turn continues down to the Gb and back up to the G in the last measure.

Either way, the chromaticism in the turn, totally contemptuous of the key signature, is a large part of what gives it “gypsy” flavor. A more classical turn might keep the same kind of rhythm and shape, but would more likely use notes within the key signature.

So how do you integrate this into your playing?

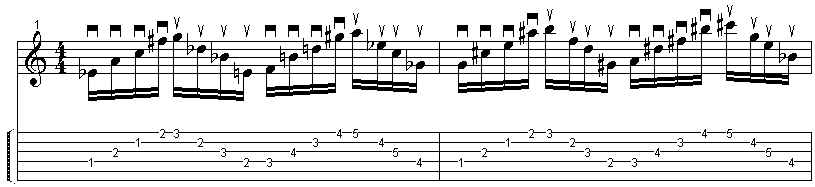

First of all, a great type of chord progression to use this on would be a gypsy-type version of that old standard, “Bei Mir Bist Du Schein”. This song is, in it’s simplest form, a 3-chord song consisting of just Am, Dm and E7. However, we’ll jazz it up by substituting a progression involving m6 chords for the Am, and adding an F7 at the end of the form just to spruce up the turnaround. Here’s how the chords go in the A section:

| Am6 Bm6 | C6 Bm6 | Am6 Bm6 | C6 Bm6 |

| E7 | E7 | Am | F7 E7 |

Try improvising over that, starting each phrase with the turn starting on various notes. Which starting notes work the best? (my favorites are E, A and C in that order – the notes of the root chord, even when the other chords are sounding). See what you can come up with! And then try integrating the turn into the middle of phrases – that’s when the chromaticism really comes alive.

etc.

etc.

etc.

etc.